Who Were

The Cambs

The Cambs

at War

1/1st Btn 1914-1919

1914 - 1/1st Overview

1915 - 1/1st Overview

1915 - St Eloi

1915 - Fosse Wood

1916 - 1/1st Overview

1916 - The Schwaben

1916 - St Pierre Divion

1917 - 1/1st Overview

1917 - St Julien

Insignia, Medals & Books

Remembering The Cambs

Biographies

About Us &

This Site

Rifle Grenades, Mines and Raids - May to August 1916

May

The beginning of May found the 1/1st Cambridgeshire Regiment (118th Brigade, 39th Division) in billets at Gorre, and providing working parties to assist the Royal Engineers in the Givenchy-lez-la-Bassee sector. This was just north of the La Bassee Canal and considered a quiet sector. Here both the British and Germans were digging tunnels to explode mines under their opponent’s lines; the ground would become pitted with more mine craters.

On May 5 the battalion moved into Givenchy’s left sub-sector (known as B2). Casualties were incurred immediately and continued throughout the month, mainly from German rifle grenades. By the time they were relieved on May 9, two men (Pte Reg Runham, of Whittlesford, and Pte Percy Mansfield, of Cambridge) had been killed, and Pte James Creek, of Whittlesford, was to die of wounds. Many others were wounded.

Next the battalion spent several days in the Village Line at Givenchy, again providing working parties, but were back in B2 on May 13. Six more men were killed by rifle grenades by May 16. These short periods of front line and support duty continued until the end of the month.

For two months the units of the 39th Division had been under scrutiny and several battalion commanders, including Lt-Col G L Archer, of the Cambridgeshires, were removed. A pre-war Territorial Force officer from Ely, Archer had on February 14, 1915, gone with the battalion to the Western Front as second in command, and, in April 1915, had succeeded Lt-Col C E F Copeman as commanding officer. It was felt Archer “lacked power of command” and that “the continual strain of over one year’s trench warfare has begun to tell upon him and he requires a rest.”

So it was that Archer was euphemistically “invalided home” on May 30, transferred to the TF Reserve and eventually given command of the home service 4/1st Cambridgeshires in April 1917. In The Cambridgeshires 1914-19 by Riddell & Clayton, it is stated that “All we knew was that we were losing one whose first thoughts had ever been for the officers and men under his command.” Temporary command was in the hands of Major Harry Few, of Willingham.

JUNE

On June 7, the 1/1st Cambridgeshires returned to B2 at Givenchy and immediately sustained two men killed and 10 wounded. That night Lt Harold Vaughan went out to an area north of what was known as ‘Craters South’, and was shot in the head by a German sniper. From South Africa, Vaughan had been commissioned into 3/1st Cambs in 1915, joining 1/1st Battalion in March 1916. Casualties continued during the month.

A new era began on June 10 when the battalion’s next commanding officer, Lt-Col E P A Riddell, arrived. ‘Ted’ Riddell was an exceptional soldier; he would be awarded the DSO twice during his time in command, and a third time after being promoted to head a Brigade in 1918. The son of a former High Sheriff of Northumberland, he was commissioned in the Northumberland Fusiliers in 1900, having already served in the Militia. Posted to the Rifle Brigade in 1908, he became an instructor at Sandhurst in early 1914 and was promoted Major the same year.

Writing in The Cambridgeshires, Riddell recalled a warning that his new role would be a “stiff job” but subsequent events would prove the verdict was a “hopelessly inaccurate” view of the battalion, because, as he added: “Nearly four months later they had made history.”

The same day coincided with a commission for their Regimental Sgt-Major, Ben Pooley, as the battalion’s new Quartermaster. A stalwart of the regiment, Pooley had joined the 3rd (Volunteer) Btn The Suffolk Regt in 1895, served in the Boer War, and transferred from the Volunteers to the new Cambridgeshire Regiment in 1908, becoming the Colour-Sgt of A Company. Pooley, a Post Office engineer in Cambridge, sailed to the Western Front with the battalion in February 1915 and was soon promoted RSM. Finishing the war with the rank of Captain, he served with the regiment in the 1920s, retiring with the rank of Major in 1932.

Riddell found his new command “a well-disciplined unit” and was particularly impressed by B company and its young commander, Captain Eric Wood, who as a student at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, had in October 1914 gained a commission in the battalion.

“Men who held the Givenchy, Festubert or Ferme du Bois sectors of our line during the months of June and July of 1916, and survived, will recall the extraordinary circumstances under which we lived,” Riddell recalled in The Cambridgeshires.

Describing the ground, he added: “Except for the hill at Givenchy, we had no trenches on the battle-front. Germans and British held lines of sandbag forts, which stood out white and glaring in contrast with the bright green of the high grass covering the dead level plain. If either side had so desired, these forts could have been obliterated by artillery fire in a few minutes.”

The poet Edmund Blunden, serving in 39th Division as an officer in 11th Royal Sussex (116th Brigade) described the islands as lonely sandbagged strongpoints built above waterlogged ground. Six to 800 yards behind the British ‘forts’ was their second, or Village, line.

On June 11, the Germans had exploded a small mine under J Sap, which was successfully held men of B company. Their efforts were recognised by Military Medals for L/Cpl Joe Franklin and L/Cpl Martin Pleasance, both from Cambridge, who reorganised their men and consolidated the new crater’s near lip. Later that day the battalion moved into the Village Line and there remained until June 17.

Five days later the Cambridgeshires would have heard about the explosion of a German mine under part of the line held by 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers, causing a crater 120 yards long, 70 feet wide and 30ft deep – the largest on the Western Front at that time. In honour of its defenders, whose cap badge featured a dragon, it was named the Red Dragon Crater.

The Cambridgeshires were back in the line on June 28 at Ferme du Bois, with plans well known of a ‘Big Push’ being planned by the British and French further south on the Somme. Elsewhere troops were required to make diversionary attacks so the Germans would not be tempted to send reserves to the main offensive.

For the 39th Division, it was the 12th and 13th Royal Sussex Regiment (116th Brigade) that on June 30 attacked a salient known as the Boar’s Head. After initially going well, the Sussex attack broke down. On their right, the Cambridgeshires, who assisted with bursts of rapid fire, were hit by German shelling; they sustained two killed and 16 wounded, and later men spent the night searching for wounded Sussex troops in No Man’s Land.

JULY

While on July 1 the big offensive started further south with massive British casualties, the Cambridgeshires left Ferme du Bois for a short rest, before returning on July 4. Daily casualties continued until they moved into Brigade Reserve on July 8. Four days later the battalion went into the line at Festubert. Regular patrols to check German dispositions continued, and during one on July 18, Capt Roger Tebbutt, of A coy and son of pre-war commanding officer Lt-Col Louis Tebbutt, was 30 yards from the enemy wire when he was wounded by a bullet. His brother Oswold had been among the battalion’s casualties near Ypres in 1915.

During the night of July 18/19, a strong fighting patrol of nearly 120 men was made by the battalion into the German lines to obtain prisoners and identifications. It coincided with nearby efforts by 1/1st Herts and 1/6th Cheshires, the latter’s at the Red Dragon Crater, where they drew away German fire from the left of the Cambridgeshires, thus reducing their casualties.

Riddell had selected Capt Eric Wood to lead the battalion’s raiders, who, with their faces blackened, attempted to enter the German lines at various points during a bombardment, but found the knee-high wire impassable. A group under Lt George Herman cut through to the parapet; it is thought the officer got into the German trench but was not seen again. Another officer, Lt Guy Rawlinson, was also seen cutting wire for his party, but was wounded and taken prisoner, dying of his wounds on July 23. 2nd Lt Arthur Looker was severely wounded in his hands, stomach and a foot, but kept the Germans at bay as the thwarted attackers retreated. One other rank (Pte Charles Bowyer, of Cambridge, nephew of another stalwart, Sgt George Bowyer, who had recently transferred to the 118th Brigade Machine Gun Company) was killed and six wounded.

The gallantry was recognised with a DSO for 2nd Lt Looker (an Australian living in South Africa who in 1915 was commissioned in the Cambridgeshires), while Capt Wood was awarded the MC. There were Military Medals for Sgt Percy Denyer, Pte George Smith and Pte George Jugg. Smith had recovered Bowyer’s body from the German wire.

On July 20, 2nd Lt Alan Jameson, who had been a schoolboy at Denstone College with Eric Wood and a student at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, was killed. Four days later the battalion moved to the left sector at Givenchy and came out of the line on July 26.

AUGUST

After a few days’ rest, on August 1 the Cambridgeshires moved into Festubert’s Village Line and then on August 7 into the left sub-sector. Pte Walter Rowe, of Wisbech (brother of Sgt Fred Rowe DCM), was the battalion’s last man killed in this area. They were relieved on August 10/11 by battered troops pulled out of the Somme, the next destination for the 39th Division.

“The days of little fighting and quiet sectors soon ended; for August found us tramping our way south by easy stages to the Somme shambles,” wrote Riddell. In the last week of August the Cambridgeshires were about to enter the Battle of the Somme, where they would make history.

Back to the top of the page.

James Creek from Whittlesford.

Lt Col Archer while CO of the 4/1st Bn.

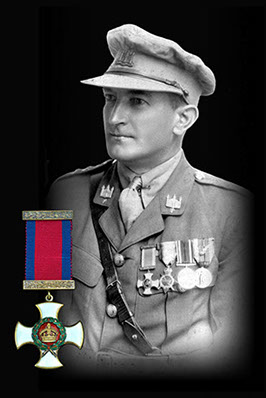

"Ted" Riddell later on in the War.

Ben Pooley just before being commissioned.

Capt Wood before the award of his MC.

Looker DSO, taken after the War.

This site went live on the 14th February 2015 to mark 100 years since the 1/1st Cambs went off to war.

WE WILL REMEMBER THEM

Email us: cambsregt@gmail.com

Copyright 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 by Felix Jackson. The information and images on this site should not be reproduced without prior permission.